S.C. ends fiscal year with unprecedented $1.024 billion surplus

August 13, 2021Comptroller warns of ticking time bomb in state pension plans

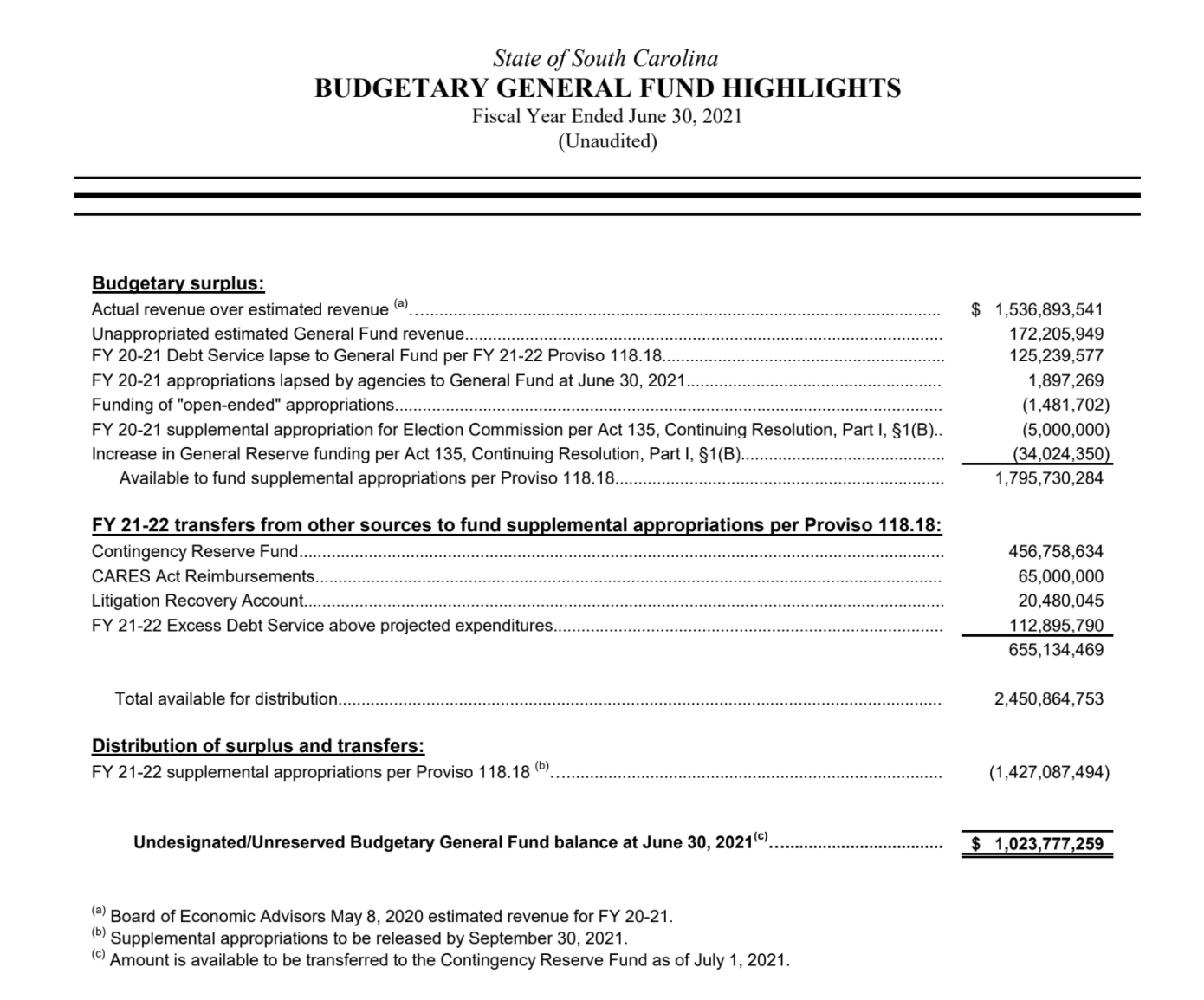

The S.C. Comptroller’s Office closed the books on state government’s fiscal year that ended June 30, 2021 (FY2021) with a $1.024 billion General Fund surplus. The state’s General Fund spent $8.4 billion in FY2021, the majority of which was underwritten by income tax and sales tax collections. FY 2021’s General Fund spending declined 2.7% (or $0.235 billion) compared to amounts spent in FY2020, while FY2021’s General Fund revenues topped FY2020 revenues by 13.9% (or $1.280 billion).

Most of the $1.280 billion increase in General Fund revenues resulted from increases of 16.4% (or $0.539 billion) in sales and use tax receipts, 8.6% (or $0.384 billion) in individual income tax receipts, and 66.3% (or $0.248 billion) in corporate income tax receipts.

Actual revenue collections for the year were dramatically higher than revenue projections that were used at the beginning of the year. As a result, near the end of the year budget writers crafted a $1.427 billion supplemental spending bill by using emerging surplus revenues and available funds from other sources. The bill authorized more than $1.2 billion in “wish list” spending for state agencies, colleges, and universities, and it earmarked the remainder to be distributed to numerous nonprofit and community-based organizations throughout the state.

The General Assembly possesses the sole authority to make budgeting decisions for S.C. state government. Normally those decisions relate to annual requests each state agency makes to the General Assembly for funds to cover the agency’s recurring operating budget. This budgeting process spans a four to five month period during which budget requests are presented and defended by agencies, extensively discussed and debated by legislative budget committees, and ultimately approved after additional debate in the two chambers of the General Assembly where any remaining differences between the House version of the budget and the Senate version are reconciled. This process produces the state’s recurring annual operating budget.

The state’s annual operating budget, which authorizes spending, is enacted into law prior to the beginning of a new fiscal year, which means that the budget must be based on best estimates of revenues the state expects to receive during an upcoming year. Typically these estimates are close to what the state collects. If they’re too high, it can necessitate painful and difficult-to-absorb midyear budget cuts, which is why so much debate centers around the annual operating budget. On the other hand, if actual revenue collections exceed estimated revenue collections used as the basis for the operating budget, the General Assembly has “extra money” that it often tends to spend with very little, if any, discussion or debate.

FY2021 was unique in the history of state government. It was certainly unique because of the great uncertainty created by COVID-19. Yet it was also unique because the year produced such enormous levels of surplus revenue, which resulted from the state’s actual revenue collections far exceeding the revenue projections used for the FY2021 budget.

As a result of growing surplus projections that became more predictable as the year progressed, the General Assembly passed the aforementioned $1.427 billion supplemental spending bill. As previously noted, this massive supplemental spending package included funding for discretionary “wish list” projects and “earmarks” for organizations outside state government. Yet in lieu of “wish list” spending, this would have been an ideal year to begin dealing with both the growing $29 billion deficit in the state’s five retirement plans and the $18 billion deficit in the state’s retiree health insurance plan, although these deficits were not addressed. While public employees have already earned the retirement benefits promised through these plans, the plans are collectively underfunded by $47 billion.

This represents $47 billion of debt, which the state continues to ignore while the debt incessantly grows. “It’s a ticking time bomb and a financial train wreck happening in slow motion,” says Comptroller General Richard Eckstrom.

Other states have recently begun to confront deficits in their retirement plans. For example, the state of Kentucky is making special cash contributions into the KY Teachers’ Retirement System that have amounted to $529 million in FY2017, $1.6 billion in FY2018, $1.05 billion in FY2019, and another $1.05 billion in FY2020. While the states of Tennessee and Idaho are facing plan deficits much smaller than ours, both of them have recently increased employer contributions to reduce their plans’ deficits.

This would have been a very logical year to have committed a significant portion of our surplus revenues to start paying off our $47 billion deficit. Possibly part of this liability can be passed along to local governments and other nonprofit entities whose employees participate in the state’s plans. “But the fix will cost money,” Eckstrom states, “and the longer the state delays the fix the larger the deficit will become because it’s growing by the year.”

“A starting point would be to earmark all, or at least a significant portion, of the available $1.024 billion of year end General Fund surplus, which I’m announcing today, to make special contributions into SCRS (which includes teachers and other public employees) and PORS (which includes law enforcement officials and firefighters). In addition to this unobligated surplus, there is currently $0.524 billion in the Contingency Reserve Fund that could be earmarked to apply against the state’s retirement benefit deficits. These would be transparent earmarks that ought to endure close public scrutiny” said Eckstrom.