The Luck Of The Draw

February 14, 2024By Tom Poland

December 1, 1969, was no ordinary Monday. It was a day when your birthday was your destiny. In Athens, Georgia’s Benton Apartments my roommates and I were glued to the TV. CBS correspondent, Roger Mudd (His name really was Mudd), was covering Nixon’s draft lottery. We were mired in the bell-bottom, LSD, hippie times, and a war 9,000 miles away. Ninety minutes was about to change the life of half a million men.

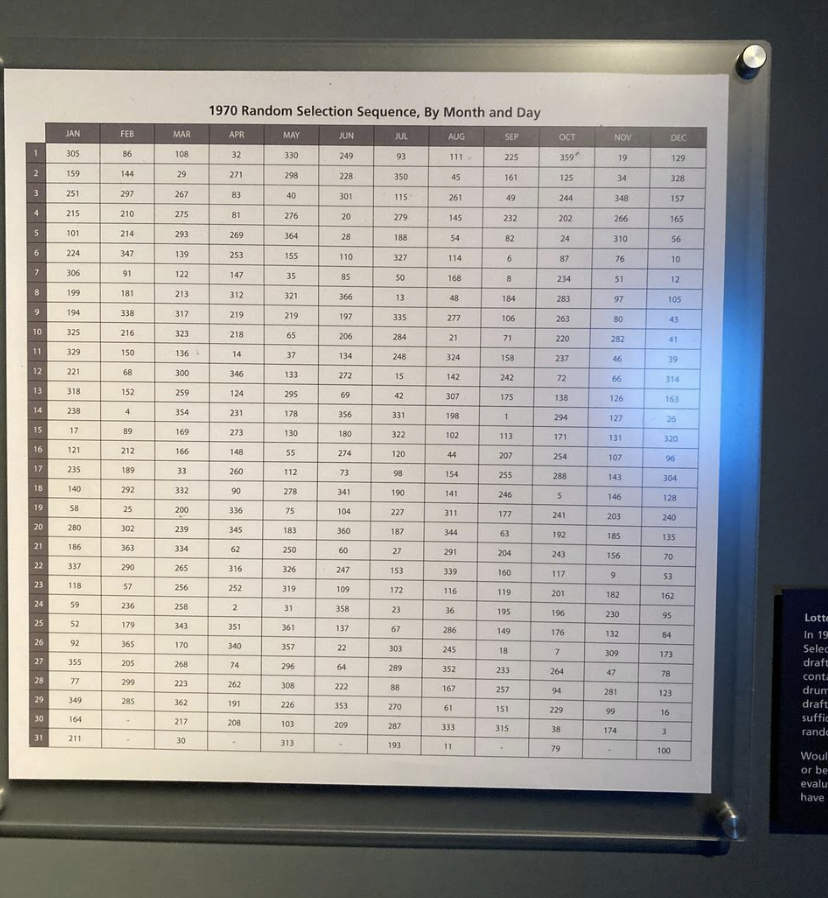

A tumbler held plastic capsules with a date in each that ran from January 1 to December 31, and yes, February 29. The draft call ceiling was 195. If you drew 196 or higher, you would not be drafted.

A calendar of sorts like no other.

There’s this saying, “When your number’s up, you’ll know it.” We would know tonight. The first number drawn, September 14. The second, April 24. Out came more numbers. A roommate’s number was up. May 6 drew lottery number 155. He wasn’t happy, with reason. If you were from a small town where few draft-eligible men lived, the draft would gobble numbers. If you were from a big city, a surfeit of birthdays provided a degree of protection.

If you were poor, of no connections, you just might find yourself conscripted into service. Some used connections to dodge the war. This imbalance wasn’t lost on John Fogerty of Creedence Clearwater Revival. He wrote “Fortunate Son” in 1968. Among its lyrics: “I ain’t no senator’s son … I ain’t no fortunate one.”

Nor was I. Dad said he would send me to Canada if I got drafted. I would have refused his offer. Some fellows entered the National Guard and others chose careers that would exempt them from service. Some did, indeed, flee to Canada. Some, as Fogerty knew, used their connections.

In his memoir, John Fogerty said he had David Eisenhower in mind when he wrote “Fortunate Son.” President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s grandson, David Eisenhower, married Julie Nixon, the daughter of President-elect Richard Nixon in 1968. Fortunate David spent three years in the military, most as an officer aboard the USS Albany in the Mediterranean Sea. It took an angry Fogerty just 20 minutes to write the lyrics.

In Benton Apartments, a cluster of gray concrete block dwellings, several young men stared at a small black-and-white TV. July 4 brought number 274. November 11, Veterans Day, came up as number 46—veterans-to-be were on their way to service. December 25 brought a gift, 84. “Merry Christmas, you’re in the Army now.”

My birthday, February 4, drew 210. My grades took an immediate nosedive. That led to academic probation, and that led to summer school, and that led to a series of events that changed my life forever—in a good, bad, and ugly way, as Eastwood’s movie title went.

All that was 54 years ago. Now and then when in Athens, I drive by Benton Apartments. Among the few memories I retain from there are rumors of Paul McCartney’s death and Nixon’s draft lottery. The rumor proved untrue, of course, but the lottery’s effect would reach far down the road. As close as I would come to military service were two years in Air Force ROTC. Come Thursdays we’d shine our shoes, don our wool uniform, and march in the parking lot behind the University’s coliseum. Twice a week we attended classes on rockets and airplanes.

In the years to come I would meet gunship pilots and women whose husbands had served in Vietnam, some of whom carried heavy burdens. The luck of the draw had kept me out of all that, but as I aged I felt shame. To this day I wonder what kind of man I might have become had I served over there. I missed something major. Honor in service, for one thing. Maybe I wasn’t as fortunate as I thought, but I am still alive, and I thank those men for their service in Vietnam, you unfortunate brave sons who deserved far better treatment than you received.

Georgia native Tom Poland writes a weekly column about the South, its people, traditions, lifestyle, and culture and speaks frequently to groups in the South. Governor Henry McMaster conferred the Order of the Palmetto upon Tom, South Carolina’s highest civilian honor, stating, “His work is exceptional to the state.” Poland’s work appears in books, magazines, journals, and newspapers throughout the South.

Visit Tom’s website at www.tompoland.net

Email him at [email protected]