At 19, Dennis DuPuis flew helicopters in combat in Vietnam

February 7, 2024Dennis DuPuis wasn’t the only soldier in his family to serve in Vietnam. His father, an Army Signal Corps master sergeant who had served in the Second World War and Korea, volunteered to go to Vietnam hoping Gen. William Westmoreland was right about “the light at the end of the tunnel,” and that his boys wouldn’t have to go. About six weeks after his Dad got back, his older son Bruce arrived in-country as an infantry lieutenant, a MACV advisor.

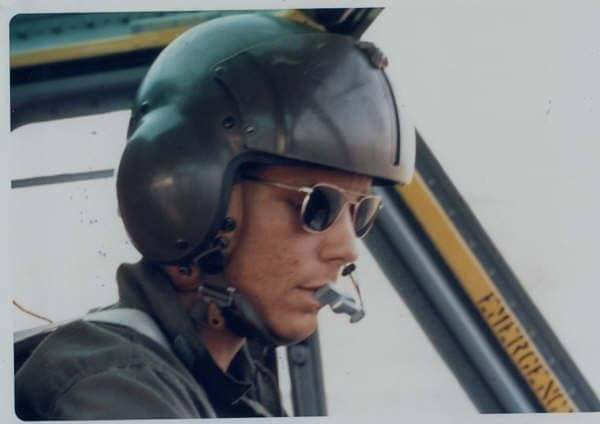

Dennis tried college after high school, and it didn’t suit him. So he joined up – but not for the infantry. He enlisted for flight training. His father and the whole family were very proud of a cousin who had died in Burma with the Flying Tigers, “I just wanted Dad to be that proud of me,” remembers Dennis. The Army needed lots of helicopter pilots in Vietnam, so in August 1969 after a year of training, he arrived as a warrant officer to fly Hueys with an assault helicopter company in the Delta. He was 19 years old. He turned 20 later in the month.

He will tell the story of his two tours in Vietnam in a free lecture at noon on Friday, Feb. 16, at the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum in Columbia. The program, which he calls “From High School to Flight School,” is open to the public, and is presented in connection with the museum’s sprawling, unique exhibit, “A War With No Front Lines: South Carolina and the Vietnam War, 1965-1973.” It is part of the museum’s regular Noon Debrief series.

DuPuis would see a great deal of action over and on the ground in Vietnam – and Cambodia as well. A sample from the timeline of his experiences he once wrote for the Veterans’ Administration goes like this:

1970 May 1: The Cowboy flight of 10 slicks and 3 guns approached the east side of the Mekong River, about 25 klicks south of the Cambodian border. There were hundreds of huey’s in the air, more than I had ever seen. Today we were invading Cambodia. On our approach to the air strip, I saw more hueys parked on the ground. There were heavy lift Chinook companies, Cavalry units, Cobra Attack companies, and many Assault Helicopter Companies like the 335th AHC Cowboys, within the perimeter guarded by armored personnel carries; and there was infantry, a lot of ARVN infantry. We landed. The helicopters stretched for as far as I could see. The size of this operation excited and scared me at the same time…

That was the incursion that sparked the protests at Kent State University. But DuPuis had been in Cambodia months earlier, just over the border, during a confusing night combat assault in which another Huey in his flight crashed and burned at the LZ.

He saw a great deal of action, and saw friends die. He heard about others. His best friend George Mason was killed flying a Chinook far away in I Corps. George’s mother requested that Dennis be allowed to accompany the body to the Mason home in Oklahoma, which he did. Then, after a quick trip home, he was back in Vietnam.

Not long after, a new pilot joined the unit, and it was DuPuis’ job to assign him to a helicopter. But first, Dennis noticed something – the young man, Donald Krumrie, was wearing a hat that said “Enid, OK.” That’s where Dennis had just been, for George’s funeral. He told Kumrie about that, and it turned out Krumrie’s mother had been at the funeral.

He assigned Krumrie to a good crew for his first mission as an aircraft commander. But in his VA timeline, DuPuis would later write:

17 July 1970 -Only TWO weeks until I return to the World (the USA). I am the platoon scheduling officer. I assign a pilot to his first pilot-in-command combat assault. By mid day, he is dead and on his way home in a body bag. RIP Donald Krumrie

Not long after, he went home. But a year after that, at the age of 21, he returned to Vietnam to fly Cobra attack helicopters for the 101st Airborne/Airmobile Division.

He has a lot of stories. Come listen at the Relic Room on Feb. 16.

About the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum

Founded in 1896, the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum is an accredited museum focusing on South Carolina’s distinguished martial tradition through the Revolutionary War, Mexican War, Civil War, Spanish-American War, World Wars I and II, Vietnam, the War on Terror, and other American conflicts. It serves as the state’s military history museum by collecting, preserving, and exhibiting South Carolina’s military heritage from the colonial era to the present, and by providing superior educational experiences and programming. It recently opened a major new exhibit, “A War With No Front Lines: South Carolina and the Vietnam War, 1965-1973.” The museum is located at 301 Gervais St. in Columbia, sharing the Columbia Mills building with the State Museum. For more information, go to https://crr.sc.gov/