I Am Lander 150: The educational influence of Samuel Lander continues

April 11, 2022In the early 1870s, Grace Methodist Church in Williamston was in need of a minister. Members requested “an unmarried man who could teach.”

One can imagine the surprise — and perhaps consternation — when the minister designated for their church was the Rev. Samuel Lander. Not only did he have a wife, Laura Ann McPherson Lander, he also had seven children.

The appointment may not have been exactly what the church asked for, but it was one that would have a positive impact and change on the community and higher education history in the Palmetto State.

The immediate problem for all was the lack of a parsonage. The only vacant “dwelling” in Williamston was an abandoned hotel, once used for the thriving tourism business generated from the town’s chalybeate springs. In the years before the Civil War, tourists flocked to the springs to partake of the fresh water, believed to promote health and healing through its mineral properties. But the ravages of the war ended the community’s bustling tourism industry and closed the hotel.

The Lander family took up residence in the hotel. With a solid background as an educator and school administrator, Lander saw the opportunity to open a women’s college in his new community. The only problem was that the Methodist Church did not allow its clergymen to make a livelihood outside the pulpit.

Lander got permission to open the school. The hotel was renovated, furniture ordered, teachers were hired and advertisements were placed announcing that the school would open on Feb. 12, 1872. Lander’s skills as both an administrator and businessman became evident from the outset. By the end of the first year, enrollment had doubled from the first 36 students, and the housing capacity had been exceeded. Lander organized a stock company to enable the school to grow.

It was a bold undertaking. South Carolina was in the turbulent years of the Reconstruction era. Yet, families were eager to educate their daughters, and Lander, who had been disappointed by the lack of academic standards and work in most schools for girls, was determined to bring quality education to young women.

In a future issue of The Naiad, the college’s newsletter, Lander wrote, “We have yet to learn that the higher education, like every thing (sic) else of superior worth, must be paid for according to its value. There are indications of awakened interest, larger views, and a more liberal spirit in behalf of our male schools, whereat we sincerely rejoice. What we desire is that there may be a parallel movement for our schools for girls. Let the one be done, and let the other not be left undone.”

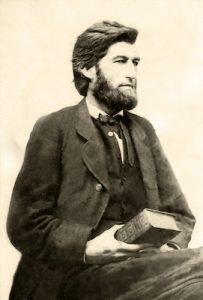

Lander knew the benefits of higher education himself, coupled with the discipline and determination to master new educational challenges throughout his life. According to an article written for the Lander family by Kathleen Lander Willson, “Heredity and environment conspired in making ready for the birth of Samuel Lander, January 30, 1833.”

His father, whose name he bore, was from Tipperary, Ireland, although the family’s ancestors were from England. The senior Lander brought his wife, Eliza Ann Miller Lander, and the family to America to escape religious persecution, and they ultimately settled in Lincolnton, North Carolina He became a successful coach maker, a profession he continued after becoming a Methodist preacher. Mrs. Lander was better educated than many women of her day and was considered an authority on European and church history. She was said to “break away from customs commonly accepted,” just as her son would do years later.

When the younger Samuel Lander was born, he was so frail that it was believed he may not live. A church bishop prayed that the infant be spared so that he might become a preacher. The prayer was answered.

Lander’s education began at age 4 with a local teacher from Charleston and continued at the Male Academy, where his uncle, the Rev. J.W. Murphy oversaw his education and introduced him to the classics, including the study of Greek and Latin, and mathematics. At Randolph Macon College, he entered the sophomore class, where he took daily walks and used the time to talk with friends about the studies which interested them. Lander believed in the importance of good penmanship, too, and he wrote in a copy book until he became an expert. The letters and papers that he left behind are a testament to this commitment.

His strong academic skills weren’t lost on the school administrators. W.A. Smith, president of Randolph Macon, wrote Lander’s father: “Dear Brother, this son of yours is a first rate boy and a first scholar of his class. … If you have any more of the same sort left, please send them on and oblige your friend.”

Lander graduated as the college’s valedictorian in 1852 and returned home to pursue civil engineering. When his brother, William Lander, encouraged him to follow in his footsteps as a lawyer, he began studies for a legal career. But the law wasn’t a fit, and he received an offer from Catawba College in Newton, North Carolina, to become a teacher. He advanced to the position of principal of Olin Academy in Iredell, North Carolina, before becoming an adjunct professor of languages at his alma mater. It was then that he earned a master’s degree.

Lander’s career as a teacher grew quickly. In 1959, the 26-year-old Lander was named president of the High Point Normal School. Licensed to preach in 1861, he became a Methodist minister in 1866. His Methodist appointments included The Lincolnton Seminary, Lincolnton Station, and the Presidency of Davenport College in Lenoir, North Carolina – posts which strengthened his administrative skills in education. In 1870, Lander was named co-president of the Spartanburg Female College.

From there, his arrival in Williamston would prove life-changing for the Lander family and the community.

In her article, Willson writes that “it requires a bold spirit to leave the beaten path and originality is often questioned – even frowned upon. But at Williamston Female College, Dr. Lander introduced several other features helpful in securing thoroughness.

Lander discovered that many students studying higher mathematics lacked knowledge of basic arithmetic or were reading advanced Latin without the ability to properly speak English, He quickly revised their lessons. All students were required to “review the elementary branches parallel with their major studies,” Willson writes. “For instance, a pupil studying trigonometry would also have regular classes in arithmetic, etc. This gave the girl before graduation a ‘refresher course’ of the subject before she graduated, in case she would teach if she went into the schoolroom.”

Among other initiatives:

- The college did not have a traditional commencement. There was no pageantry of young women in a processional line. Speeches were made, and addresses were given. But the ritual of handing out diplomas was considered frivolous by Lander. For a time, instead of a paper diploma, young women were awarded rose-gold pins to wear as a sign of their graduation.

- Concerned about the costs of education, Lander instituted tuition premiums. Those who maintained an “excellent average” could have their tuition reduced by 50 percent. Special premiums of 10 percent each also were offered in spelling and composition. An outstanding student, for example, could have her tuition reduced by 70 percent.

- In 1876, the college established a kindergarten and a class was offered to train teachers to teach young children. The only other kindergarten being offered was in Charleston.

In their book, “Lander University,” being released this month, researchers Lisa Wiecki and Dr. S. David Mash write that the healing waters of the spring, which drew tourists in previous years, became the source of Lander’s foundation for the college. Until the college moved to Greenwood in 1904, Lander wrote about the “Fountain of Health” in all issues of the school catalog, saying “that it sends forth its healing stream, free, constant and inexhaustible.”

The waters, too, were an inspiration for the naming of Lander’s journal, the “Naiad,” which was sent to those supporting the school, including alumnae. As Wiecki and Mash explain, the ancient Greeks and Romans “believed in a class of female divinities called nymphs. Various classes of nymphs included the naiads, given to the care of fountains.” Lander likened the longtime benefits of the healing waters in Williamston to the benefits that could be derived from the educational opportunities of the college. In 1884, Lander wrote, “About 12 years ago, there sprang into existence near this fount of health, the fountain of learning which since then has sent forth copious streams of mental and moral culture to gladden and adorn full many a happy heart.”

Ultimately, the college’s yearbook, published between 1923 and 1991, would be called the “Naiad.”

When the college outgrew its infrastructure in Williamston, Greenwood became the new home for the women’s college. Two months before its opening on Sept. 17, 1904, Lander died. The new school, named Lander College, honored the leadership and wisdom of its founder.

Lander’s full life and contributions to higher education were extolled in a 1908 address, given by Dr. John O. Willson, the second president, to a group of college presidents: “Beyond all doubt, Dr. Lander’s greatest success as a teacher or as a manager of a school grew out of his personality. His pure life, his refinement, his sympathy, his modesty, his enthusiasm, his openness to truth, his patience, his capacity to love and awake love, these splendid characteristics were fully developed.”