New College of Charleston digital exhibits explore untold facets of Black History in the Lowcountry

June 1, 2021Since its launch in 2014, the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative (LDHI) has worked with scholars and students to produce online exhibits, each dedicated to illuminating the Lowcountry’s forgotten histories.

With topics spanning enslaved African Muslims to Charleston’s first Latino communities, LDHI’s team believes digital interpretation can play a major role in the preservation of diverse stories.

This semester, LDHI, hosted by the Lowcountry Digital Library at the College of Charleston, has debuted two new exhibits, Hidden Voices and the Morris Street Business District.

Cannon Street Hospital and Training School for Nurses class photo circa 1900s. The hospital was established by Dr. Lucy Hughes Brown, the first African American female physician to practice in the state of South Carolina. (Courtesy of Waring Historical Library, Medical University of South Carolina)

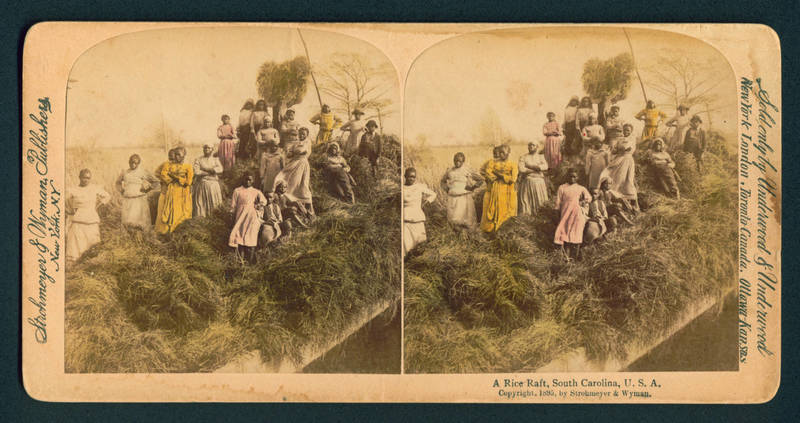

Without any context, a viewer might at first glance mistake the scene for a summer fete: Arranged in a loose pyramid, several dozen Black women and children pose outdoors in Georgetown, South Carolina.

A closer look at the caption dispels any notion of tranquility: “A rice raft, South Carolina, U.S.A.”

The hand-tinted photograph serves as the banner image of Hidden Voices: Enslaved Women in the Lowcountry and U.S. South, an exhibit exploring the complex dimensions of slavery through the lens of gender to spotlight women’s unique experiences and contributions. The exhibit tells these stories with materials drawn from collections far and wide, amplifying voices muted in the historical record.

“While slavery and enslaved people’s lives are increasingly moving to the forefront of public interest, women’s history is still sometimes relatively neglected in public representations, and it has received less focus in discussions of slavery than the lives of enslaved men,” explains Emily West, professor of history at the University of Reading and the exhibit’s author. “Yet it is vitally important to recognize that enslaved women and men experienced slavery in different ways.”

Hidden Voices foregrounds the experiences of enslaved women in the South Carolina and Georgia Lowcountry as they moved from enslavement to emancipation. West and colleagues combed the collections of repositories spanning the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture to the Library of Congress. Weaving together photographs, Work Projects Administration interviews, paintings, etchings, manuscripts, newspaper clippings and more, the exhibit is an attempt to have this history told by women themselves. They were far from passive victims in a repressive system.

“My soul revolted against the mean tyranny,” wrote Harriet Jacobs in 1861. “But where could I turn for protection? No matter whether the slave girl be as black as ebony or as fair as her mistress. In either case, there is no shadow of law to protect her from insult, from violence or even from death.”

A formerly enslaved woman with her great granddaughters, 1867. (Courtesy of the General Public Library of America)

By promoting the awareness of these stories via a digital medium, Hidden Voices represents LDHI’s mission in action.

“Black women made up over 50% of the enslaved population in the Lowcountry. With the Lowcountry’s Black-majority population, Black women were a major portion of the overall population. And because their experiences were so unique, this should be reflected in the way we retell and remember the history of slavery in the U.S.,” says Leah Worthington, Digital Projects Librarian and LDHI’s co-director.

Developing the exhibit was a great learning experience for Abbey Rice, a first-year history graduate student at CofC, who assisted in creating the digital elements of Hidden Voices.

“While working on the exhibit Hidden Voices, I gained hands-on digital public history experience, learning about the behind-the-scenes publication process,” says Rice. “It was awesome to have the opportunity to become familiar with the exhibit software, image researching and the mechanisms of writing for the public. It made me realize my passion for the digital aspect of public history.”

MORRIS STREET BUSINESS DISTRICT

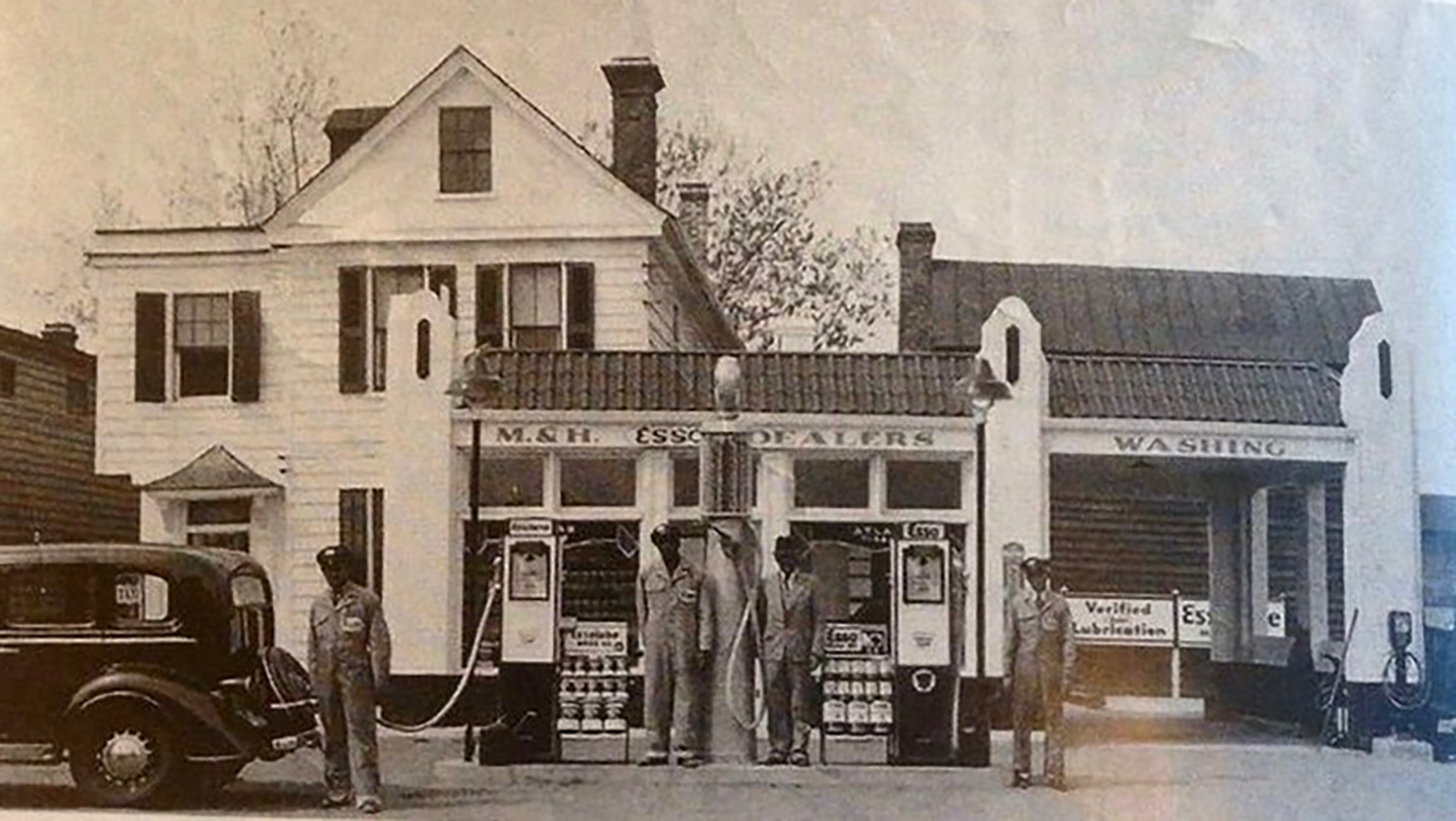

Robert F. Morrison’s Esso Station at 179 Coming Street in downtown Charleston, circa 1938.

Like many cities, Charleston is celebrated as a collection of distinct neighborhoods. Taken together, the diverse identities, stories, and communities of these neighborhoods create the city’s true character.

With its preserved and revitalized neighborhoods, Charleston trades heavily on its past. But not all history is equitably stewarded or celebrated in public memory.

For many residents, new and old alike, the Morris Street Business District is not among the most well-known neighborhoods. But this belies its vital history as the city’s heartbeat for African American communities, from the antebellum period through the 20th century.

Morris Street stretches from King Street to Rutledge Avenue, with the Business District traditionally defined as the full length of Morris Street and the blocks immediately to the north and south between Cannon and Radcliffe Streets.

In a city marked by slavery, then segregation, the Morris Street Business District provided an oasis of support and opportunity.

“Starting in the 1850s, Morris Street residents defied their political, social, economic and physical marginalization to develop a self-sustaining community with dwellings, businesses and cultural institutions,” according to the exhibit’s authors at the Thomas Mayhem Pinckney Alliance of the Preservation Society of Charleston. “It became a place where newly emancipated African Americans began their lives as free people, sent their children to school and attended religious services on their own terms.”

Picketing workers outside of the Cigar Factory building ca. 1945. (Courtesy of Georgia State University, Southern Labor Archives)

Much of Charleston’s history can be traced through the development of the district, including the successive waves of immigration from Central Europe and Asia. Its complexity charts the many ways notions of race changed in tandem with other developments in the city.

“Understanding the historical significance of Morris Street is important for a number of reasons. Its story reveals how African Americans in Charleston were able to resist slavery and its legacies during the 18th and 19th centuries through community and economic development,” says graduate student Mills Pennebaker ’19, who earned her bachelors degree in history at CofC. “Buildings on Morris Street stand out as important sites of 20th century civil rights organization, but the legacies of slavery continue to persist along Morris Street as gentrification ravages this historically important neighborhood and community.”

The exhibit features maps, photographs, illustrations, newspaper clippings and more drawn from repositories spanning the Stanford Libraries, the Avery Research Center, the Historic Charleston Foundation and MUSC.

“The history of the Morris Street Business District represents the social evolution of a single neighborhood during the most tumultuous transitional times in the history of the city, region and nation,” write the exhibit’s authors. “For over a century, the Morris Street Business District and its surrounding neighborhoods provided opportunity for people who struggled against disadvantage and prejudice — for immigrant families making their way in a new nation, and especially for Black families in their painful, powerful and ongoing struggle to gain political, social and economic equity.”