Clemson researchers study athletic performance in wheelchair tennis using motion capture technology

March 15, 2021Researchers from Clemson University are turning to motion capture technology to study the performance of wheelchair tennis athletes. The project aims to discern which wheelchair movement patterns on the tennis court are most energy efficient for the athlete while allowing them to accurately and forcefully hit the tennis ball.

The research is headed up by Jasmine Townsend, associate professor in the Clemson University Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management, and John DesJardins, the Robert B. and Susan B. Hambright Leadership Professor in the Clemson University Department of Bioengineering. Anne Marie Severyn is the lead graduate student conducting the study as part of her Ph.D. work in bioengineering.

The research is funded by a grant from the Clemson University Robert H. Brooks Sports Science Institute and is being completed in partnership with Clemson Athletics and the United States Tennis Association (USTA). Participants include players from Clemson’s wheelchair tennis team as well as recreational and elite athletes from outside the university.

Test subjects of different ability levels and experience levels in the sport donned motion capture suits to run common wheelchair tennis drills while the researchers captured data on their movements on the court. According to DesJardins, who has applied a similar study to golf and horseback riding, the hope is that the study will enhance the performance of these athletes and provide new data in this emerging area of study.

“We have had to develop an entirely new measurement model in order to study this, so it’s a first,” DesJardins said. “We hope to be able to answer questions that ultimately result in better performance from athletes, but in a more general sense we’re seeing how a person is working in concert with–or struggling against–an object such as a wheelchair in a sports setting. Maximizing what works and minimizing what doesn’t is the goal.”

Shelby Baron, a 2016 Paralympian on Team USA, was on hand to run drills during the research.

Townsend, also the director of the Clemson University Adaptive Sports and Recreation Lab, said wheelchair tennis athletes must approach the game differently than able-bodied athletes due to differences in their functional ability and the need to use a sport wheelchair. One major difference is that a wheelchair tennis athlete must remain in almost constant motion on the court; if they lose momentum, they expend much more energy to start moving again, which results in a loss of power on return hits and openings on the court that become prime targets for their opponents.

DesJardins said that this constant motion, a player’s swing and the energy required to do both all factor into how well an athlete performs on the court. The recent data collection exercise featuring multiple athletes has allowed researchers to develop a movement model that should later answer numerous questions related to specific athletes or wheelchair tennis movement in general.

“Studying multiple athletes gives us more of a universal average, but from that we can study swing mechanics or even examine the use of different tennis rackets or balls,” Desjardins said. “We can collect an amazing amount of data from these athletes in just a few minutes, and the results can help them improve their game for years to come.”

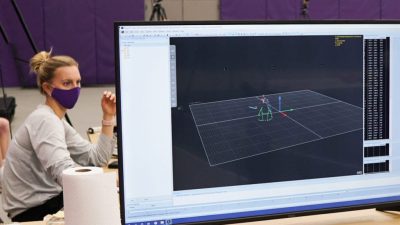

Anne Marie Severyn outputs a visual representation of captured data on a monitor for researchers to view.

Representatives from the United States Tennis Association were on hand for the data collection to ask questions about the process and to support the research. Townsend said this isn’t surprising considering how much the resulting data may reveal for athletes and coaches in the sport.

Representatives from the USTA were on hand for the data collection to ask questions about the process and to support the research. Townsend said their involvement is important considering how much the resulting data may impact athletes and coaches in their efforts toward player development at all levels. However, she said it also highlights the disparities in resource availability and development opportunities for adaptive sports in general.

Wheelchair tennis athletes, Clemson researchers, and representatives from the USTA were all on hand for the data collection. Back row left to right: Jeff Townsend, Jason Harnett, Jason Allen, Karl Davies, Zachary Harms, John Desjardins. Front row left to right: Shelby Baron, Julia Gambill, Anne Marie Severyn, Jessica Den Haese, Jasmine Townsend, Rob Popelka.

The USTA representatives said professional athletes and some college athletes receive similar assessments on performance, but the opportunity for adaptive sports athletes to examine what their bodies are doing on a biomechanical level has been rare–if it has ever happened at all before this study.

“Right now, we’re just developing the model, but we keep coming up with questions that this study could address from the player development perspective,” Townsend said. “It will be immensely helpful to see where athlete strengths and weaknesses are so that they can be improved immediately and over several training sessions. It may also shed light on how someone who has used a wheelchair their whole life might best be coached versus someone who acquired wheelchair skills later in life. We’re just excited to see where this research takes us, the athletes and the sport in general.”

The Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management is part of Clemson University’s College of Behavioral, Social and Health Sciences (CBSHS). Established in July 2016, CBSHS is a 21st-century, land-grant college that combines work in seven disciplines – communication; nursing; parks, recreation and tourism management; political science; psychology; public health sciences; sociology, anthropology and criminal justice – to further its mission of “building people and communities” in South Carolina and beyond.