Inaugural lecture series honors South Carolina’s role in civil rights history

November 9, 2021Clemson University recently held an inaugural lecture to honor South Carolina’s place in civil rights history – and to highlight the vital roles that several South Carolinians played in shaping the state and country’s drive for equality.

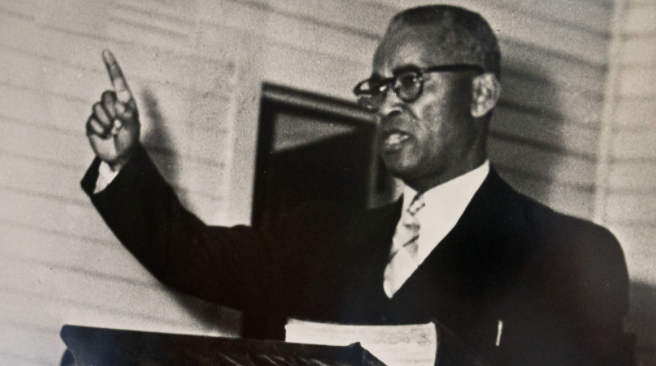

The Joseph and Mattie De Laine Lecture Series was held October 19 in the Madren Conference Center Ballroom. The multimedia event featured historical documents, historical artifacts and interview excerpts that helped shed light on the role that Joseph De Laine and his wife, Mattie, played to bring the first of five cases forward that would go on to end school segregation through the landmark Supreme Court case Brown v. the Board of Education.

Joseph De Laine Jr. attended the event and provided remarks at its conclusion.

The event was presented by the Clemson University Division of Inclusion and Equity in collaboration with Call Me MISTER®, a program based at Clemson University that works to increase the pool of Black male educators in the teaching profession. Roy Jones, executive director of Call Me MISTER, served as the primary speaker at the event, which he said was the first of many that will bring history to life for attendees and guests. Several guests the night of the event were direct descendants of those who were honored.

Jones said the lecture series was created as a major step in correctly framing South Carolina’s role in school desegregation.

“The Briggs v. Elliott suit that the De Laines helped to ignite preceded all the other cases in the Supreme Court case by more than two years,” Jones said. “A desire to distance the state from this aspect of history and the way history books can boil things down – arguably too much – can make it easy to lose sight of how citizens of this state were the catalyst for ending school segregation in the United States as a whole.”

Jones and Mark Joseph, program coordinator for Call Me MISTER, have spent years documenting interviews with individuals and descendants of those involved on both sides in the fight for desegregation. Much of this work was performed to create an archive of material and a suite of instructional materials available to educators or anyone curious about this period of history.

However, what initially seemed like a straight line to a few family members’ recollections became a branching pathway in which one source unlocked the path to more potential sources. Jones and Joseph happily “went down the rabbit hole” and emerged with enough material to justify an archive and a lecture series.

They heard stories directly from De Laine’s two surviving children, Joseph Jr. and Ophelia, who hope to attend the event. They detailed the night their father returned gunfire during a 1955 attack on their home that was retribution for involvement in the case. They later learned the attackers were a mix of police officers and Klansmen, which eventually compelled their father to escape to New York.

Joseph De Laine was born in Manning, South Carolina, and served as the principal of Liberty Hill School and pastor of the Spring Hill Circuit of the A.M.E. Church in Summerton. He encouraged a group of citizens, including Levi Pearson and Harry Briggs, to file suit in 1948 after being denied transportation for Black children who walked nine miles to schools designated for them. Joseph and Mattie worked with then-chief legal counsel to the NAACP, Thurgood Marshall, who would go on to become the first Black U.S. Supreme Court justice.

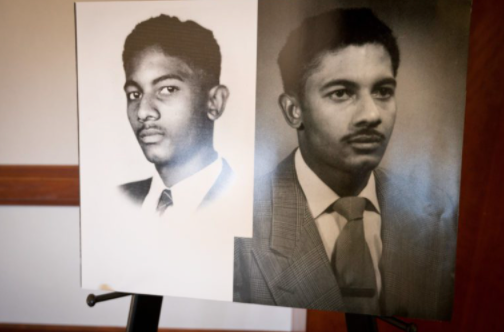

Jones and Joseph dug deeper into the petition’s origin. They learned of Reverdy Wells, the senior class president at the then all-Black Scott’s Branch High School, whose frustration with the school’s conditions motivated him to organize a group of students to present their concerns to De Laine and a group of parents and citizens that would go on to create the original petition. Wells’ story served as proof to Jones and Joseph that more often than not, the drivers of change were youth such as Wells pushing elders to, in turn, push for real change.

“It is hard to wrap your head around what it meant for these people to write their name on that petition and how it would later impact those families,” Jones said. “The De Laines and Wellses and all those petitioners paid for it in some way, whether it was to be denied employment or opportunity or to be plainly run out of the county or state.”

Subsequent interviews further motivated Jones and Joseph to establish an annual event along with a concrete way of archiving materials that were fast degrading. They wanted Clemson to become the “go-to place” for knowledge on the subject, and they set about naming scholarships for Joseph De Laine, Mattie De Laine and Reverdy Wells that would assist students from Clarendon and Fairfield counties who seek careers in education.

Lee Gill, chief inclusion and equity officer at Clemson University, said the event served to not only provide long overdue honor to many South Carolinians, but to plant a flag for Clemson as the lead player in preserving those stories and materials.

Images of Reverdy Well were on display during the lecture’s reception.

Gill was also on hand to detail future scholarships named in honor of Joseph and Mattie De Laine and Reverdy Wells that will assist South Carolina students who seek to pursue higher education at Clemson University. Preference for these scholarships will be given to students from Fairfield and Clarendon Counties, the home counties of the De Laines and Wells, respectively.

Gill said the tireless work that Jones has performed over the last several years to document this history positions Clemson as a leader in framing South Carolina history accurately and extensively. He said he is thrilled that the lives of the South Carolinians that were arguably the first to open the door to desegregation across the U.S. will be explored and examined for years to come thanks to this lecture series.

“The story of desegregation is not just Clemson’s; it is our state’s story and our nation’s story, so it is vitally important that this story is told accurately and exhaustively in the way that Dr. Jones has committed to telling it,” Gill said. “Our faculty are leading the way in this endeavor, so this is indeed a proud day for Clemson University.”