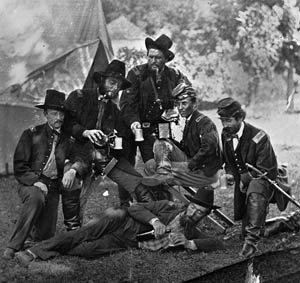

What did soldiers drink during the Civil War? Mainly, a lot of whiskey

November 1, 2021On Nov. 5, history author Tom Elmore will offer a lecture titled “A ‘Spiritual’ Guide to the Civil War.”

But you won’t need to bring your Bible or prayer book. He’ll be talking about the kind of spirits the soldiers drank.

Americans had a reputation for being heavy drinkers before the war. Elmore says that is sometimes exaggerated, but it has a solid basis in reality. After all, alcohol was safer to drink than the water in many places. The tippling became even more pronounced during the years that the nation was at war with itself.

He will share the details in his free lecture at the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum in Columbia. It will be at noon on Friday, Nov. 5, and it is part of the museum’s monthly Lunch and Learn series. Attendees are welcome to bring a lunch to enjoy while they listen.

Soldiers on both sides were fond of strong liquor, but the men in blue had better access to it. Southern distillery operations were negatively affected by the war. Not so in the North. Union soldiers were also better paid, and they had some ingenious ways of getting their hands on what they wanted.

Sailors, of course, would drink rum. In the armies, both brandy and wine – particularly champagne, and fortified wines such as madeira, sherry and port – were popular with the officers. But the average enlisted soldier reached for what was generally called simply “whiskey,” although it came in a variety of forms.

In fact, there were about eight different kinds, some of which we still see today, and others fortunately not:

• Irish whiskey was most popular. This was partly due to the influx to the North from the Potato Famine. But it was also the cheapest, and easy to find.

• Scotch was not so big in the enlisted ranks, mainly because it cost so much. Single-malts such as Glenlivet, which had been around since 1824, was big among the wealthy planters from the South.

• Rye was popular, particularly such brands as Old Overholt, which was a favorite of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s. Later, it would be drunk by Doc Holliday and President John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

• Troops from Michigan and other parts of the Midwest were partial to the Canadian variety.

• Bourbon as we know it, surprisingly enough, had not yet caught on. It had only been around in its present form for a decade or two at the time of the war.

• Moonshine made in camp, as you might expect, was quite big.

• “Sutler’s whiskey” was something you definitely “drank at your own risk,” says Elmore. There was usually a bit of the real stuff in it for flavor, but there were also such startling things as strychnine, turpentine and sulfuric acid.

Beer wasn’t as big as you might assume. In fact, the large-scale production of the popular American-style pilsener started with a Union veteran named Adolphus Busch after the war was over. You may have heard of him. He married a lady named Lilly Eberhard Anheuser.

As for the officers, William Tecumseh Sherman was very fond of madeira, and he had ample opportunity to enjoy it during his march through South Carolina. In fact, he found some in Cheraw that he judged to be the best he’d ever had. He found it there because folks in Charleston had assumed he was headed their way, so they had sent all their strong potables to places like Cheraw – and Columbia.

“Columbia was basically one big liquor cabinet,” says Elmore.

Beyond that, alcohol wasn’t all that easy to find down South. For one thing, in 1862, the Confederacy instituted “basically a prohibition,” says Elmore. The stated purpose was to encourage greater production of food, but the real motive was to stop the use of copper in distillery coils, so the metal could be used for military purposes.

The “prohibition” sort of backfired. With alcohol so popular and harder than ever to get, blockade runners started carrying booze rather than other things the South so sorely needed.

Come learn more at the museum on the first Friday of the month.

Tom Elmore holds a B.A. in history and political science from the University of South Carolina. He is the author of four books and numerous articles in regional and national publications. In addition to lecturing across the Mid-Atlantic states, Elmore has reviewed books for two national magazines. He is the current South Carolina State Historian for the Ancient Order of Hibernians. He lives in Columbia with his wife, Krys, and their chihuahua Sassy.

About the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum

Founded in 1896, the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum is an accredited museum focusing on South Carolina’s distinguished martial tradition through the Revolutionary War, Mexican War, Civil War, Spanish-American War, World Wars I and II, Vietnam, the War on Terror, and other American conflicts. It serves as the state’s military history museum by collecting, preserving, and exhibiting South Carolina’s military heritage from the colonial era to the present, and by providing superior educational experiences and programming. It is located at 301 Gervais St. in Columbia, sharing the Columbia Mills building with the State Museum. For more information, go to https://crr.sc.gov/.